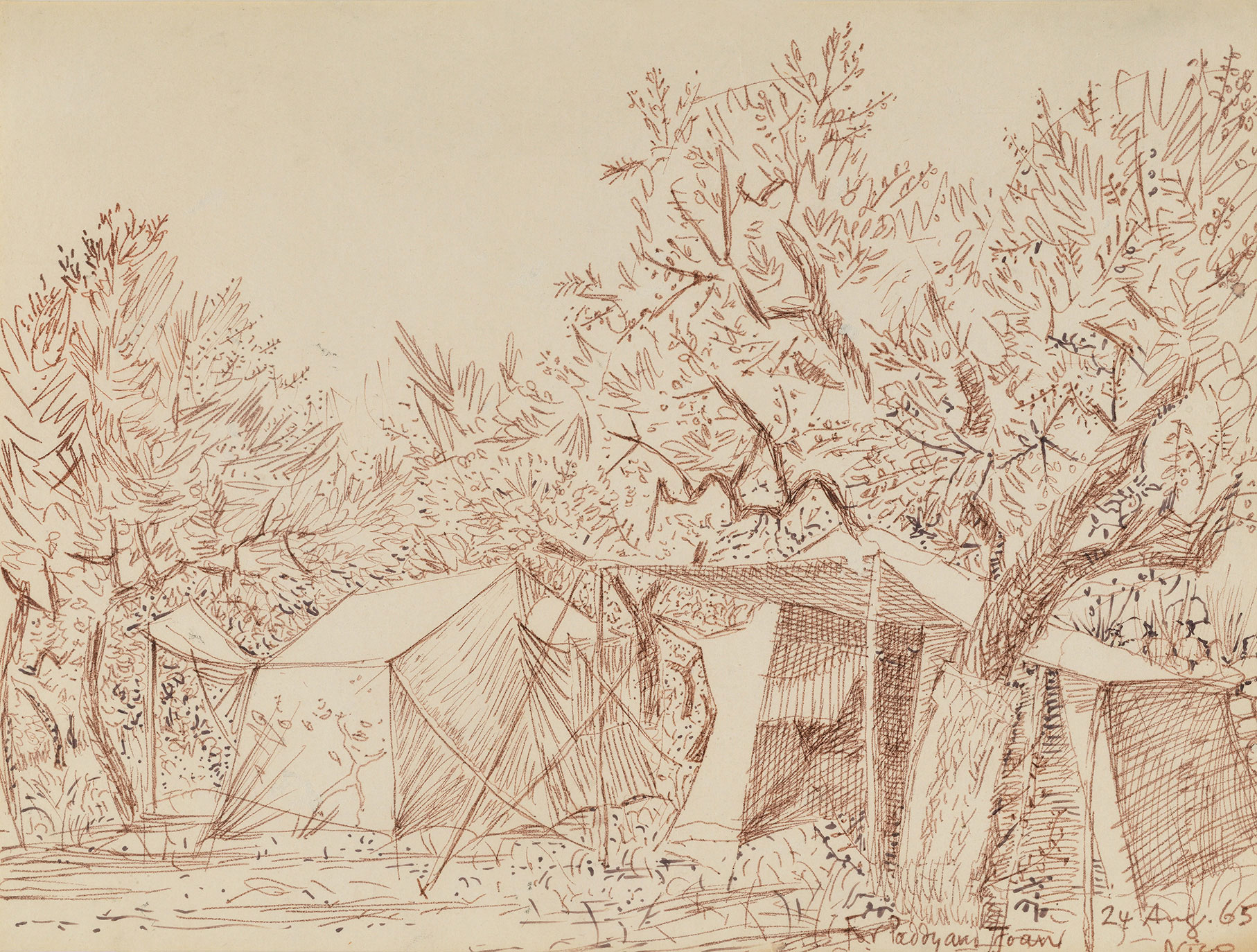

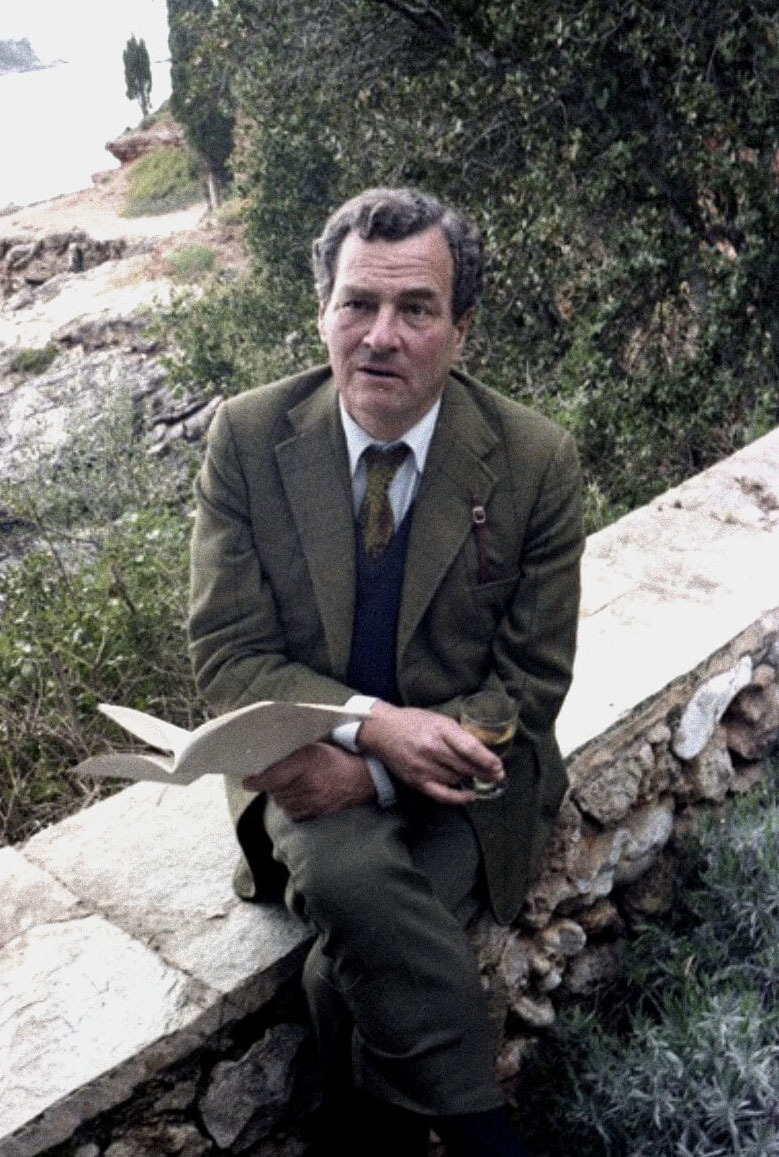

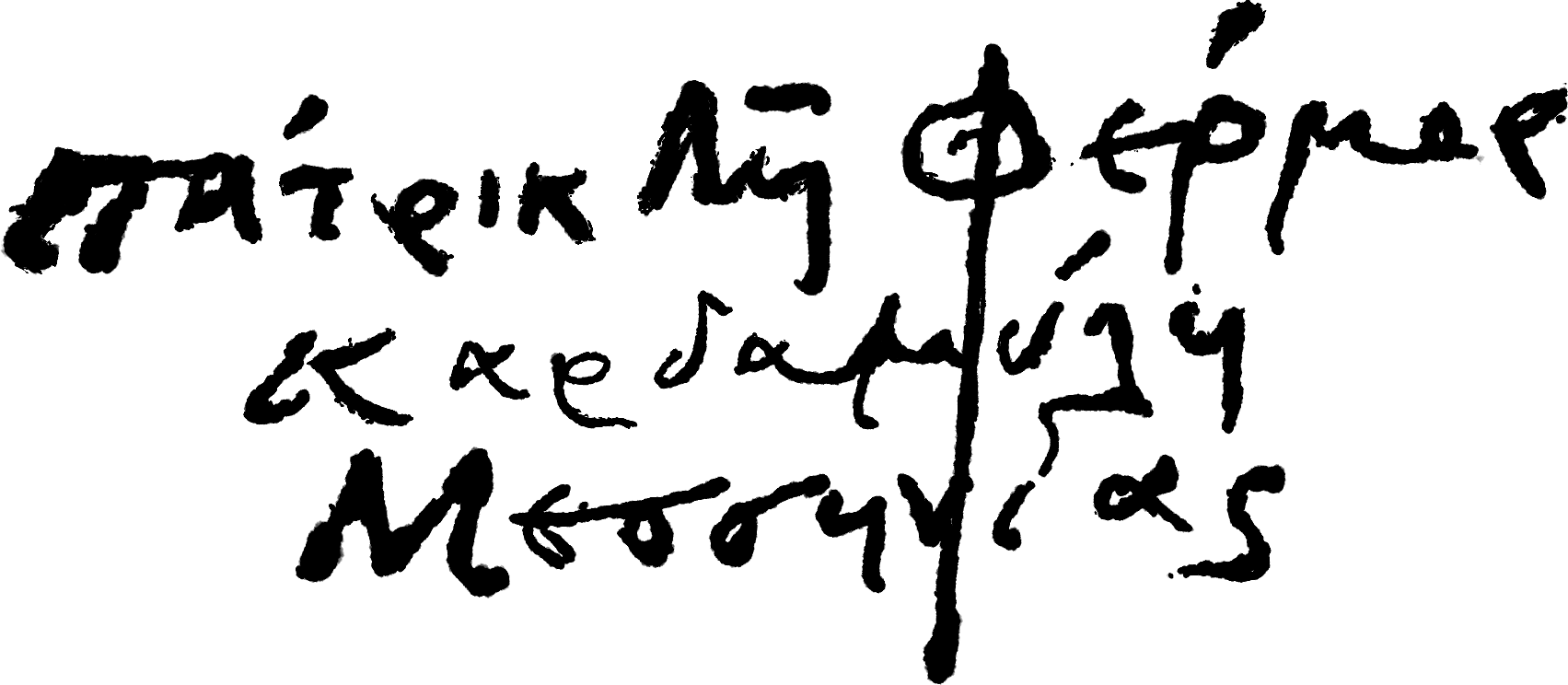

The first guest to sign the book was the architect, Nikos Hadjimichalis (1967) and among the last names is that of the former director of the Benaki Museum, Angelos Delivorrias, marking, in 2011, the start of the new era of the house.

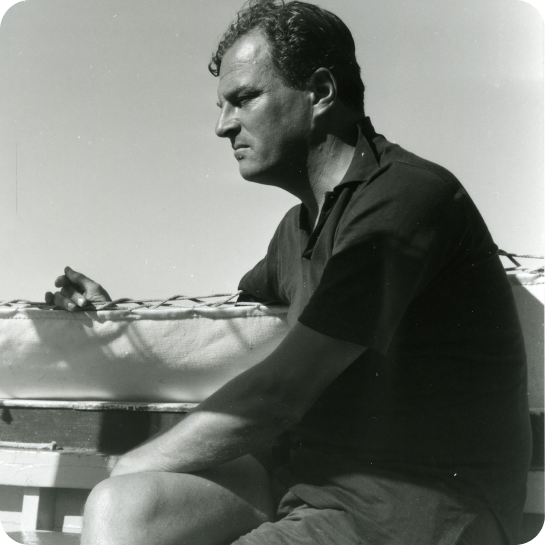

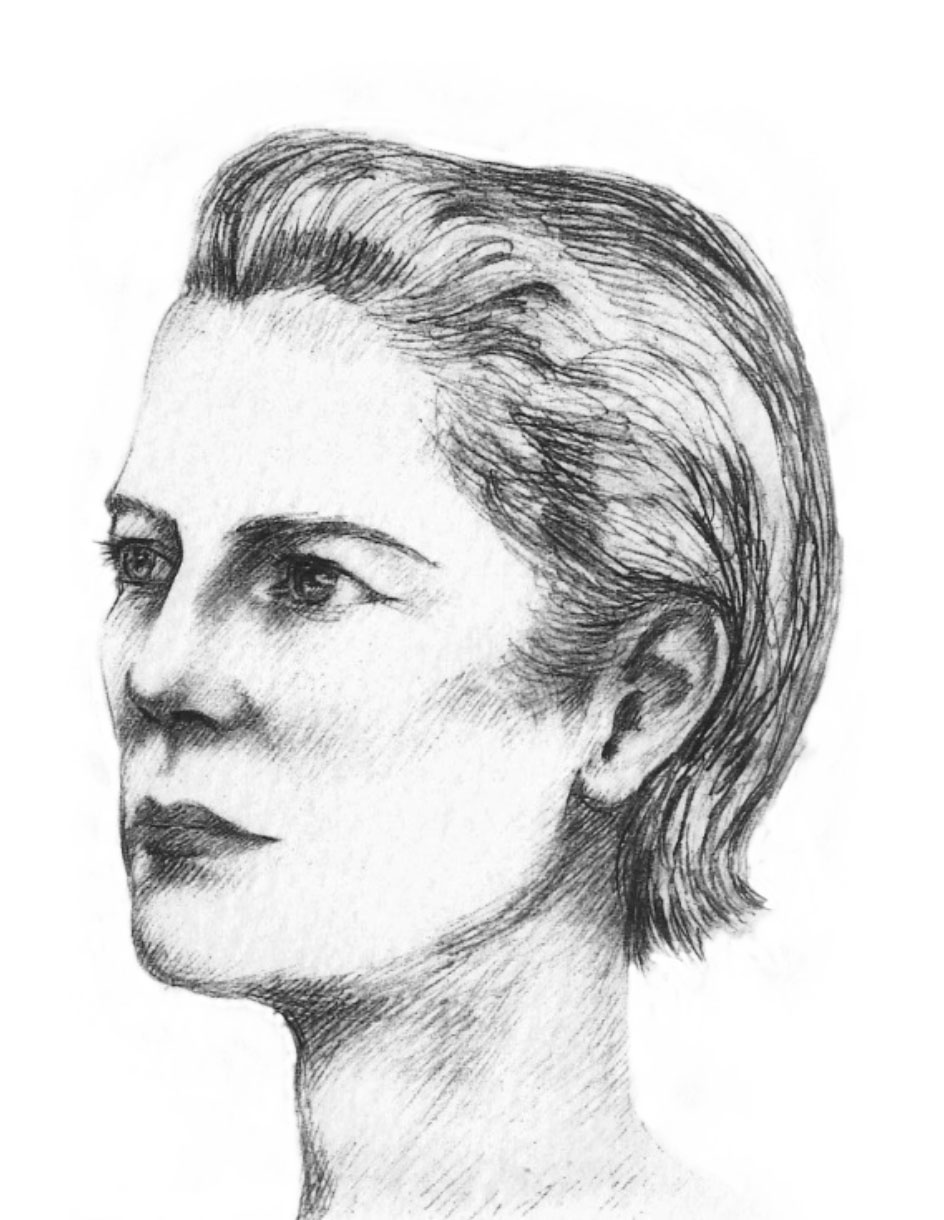

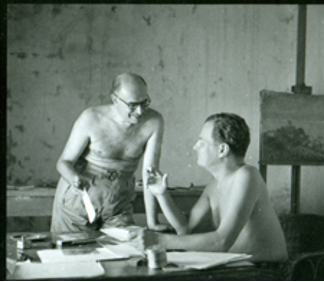

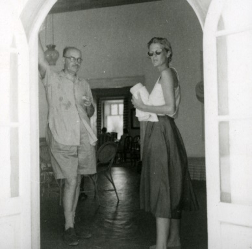

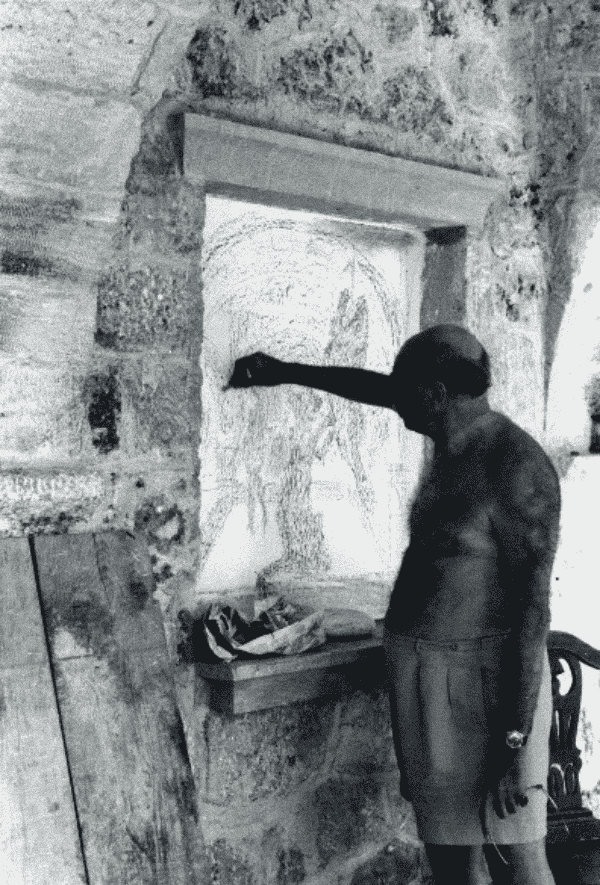

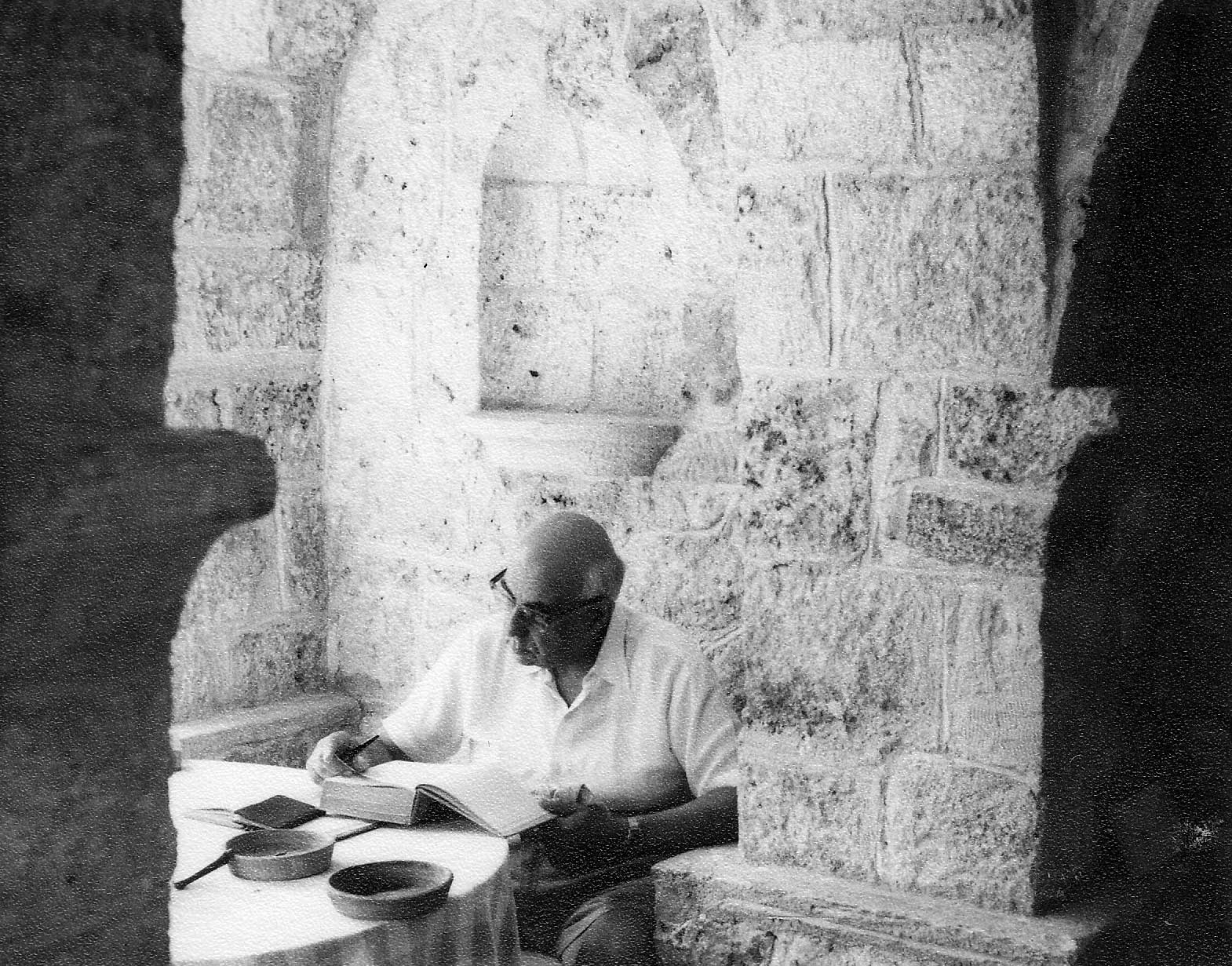

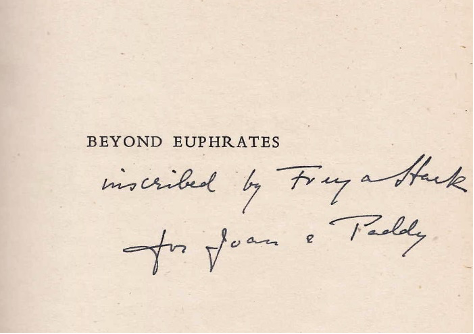

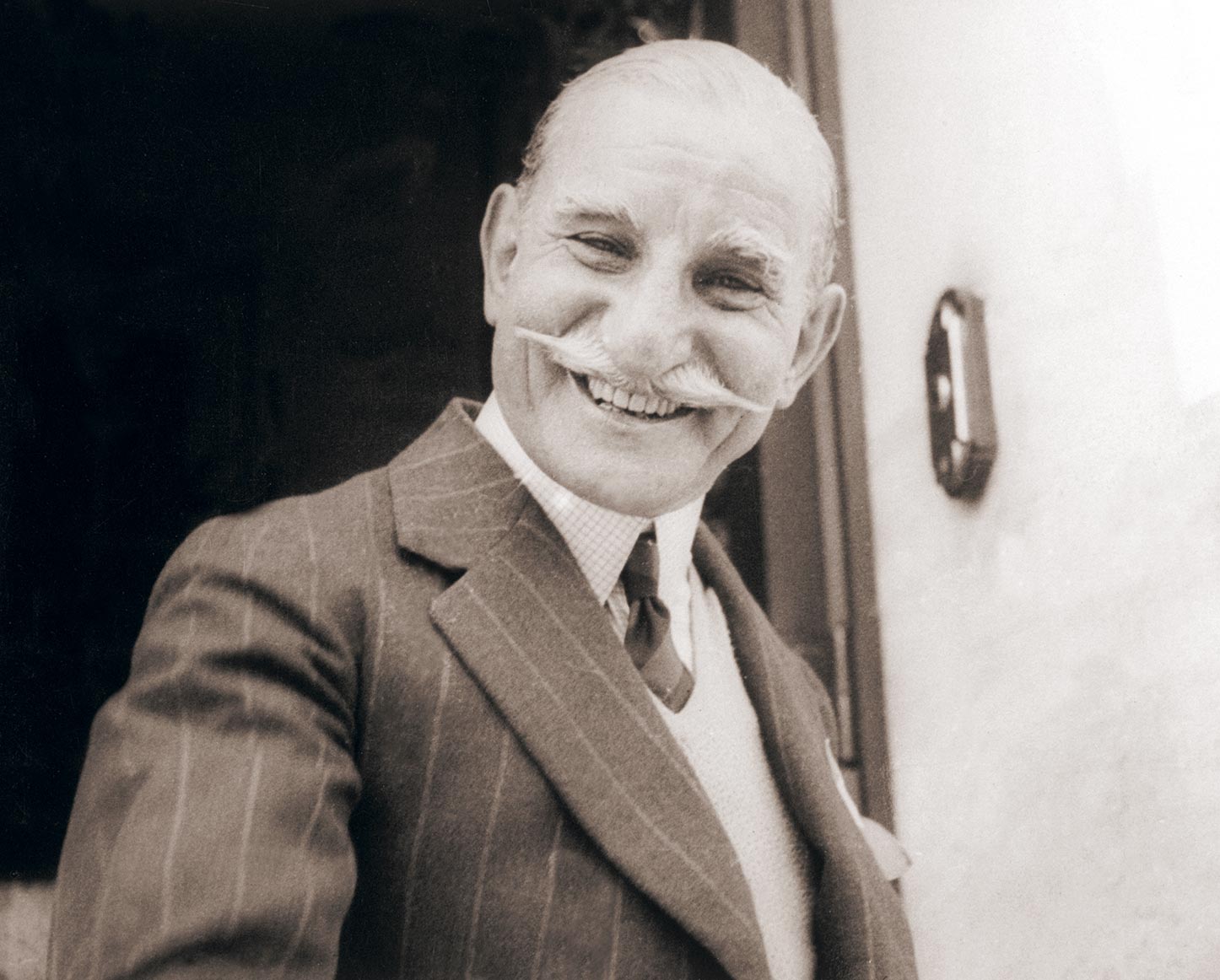

All these years, reknowed artists, scholars and writers as well as friends and relatives of the Leigh Fermors stayed at the house. Nikos Hadjikyriakos Ghika and his wife Barbara, George Seferis, John Craxton, Tzannis Tzannetakis, Freya Stark, Steven Runciman, Lord Jellicoe, John Betjeman, Bruce Chatwin, and many others.

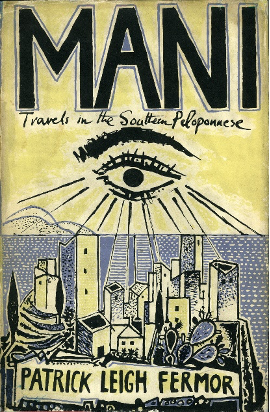

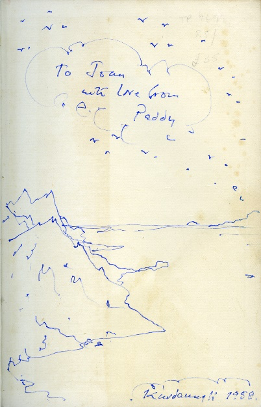

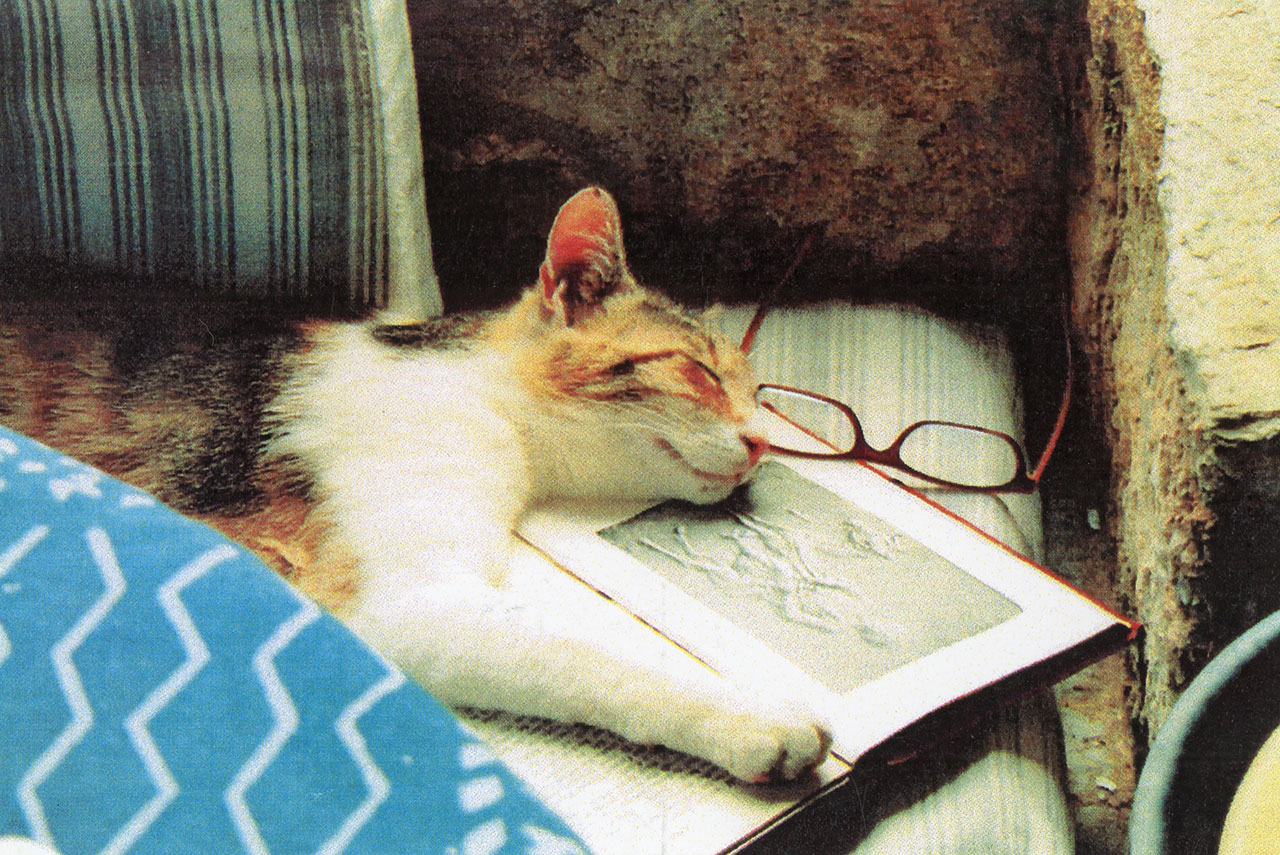

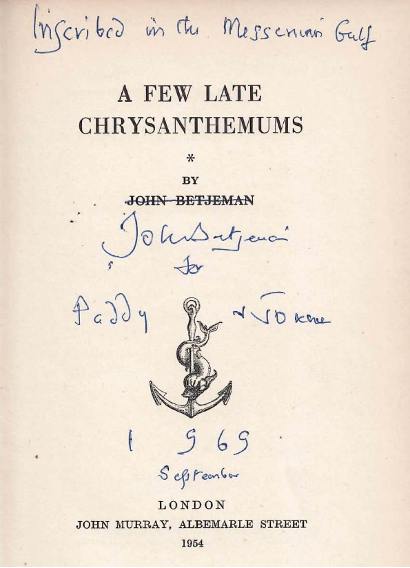

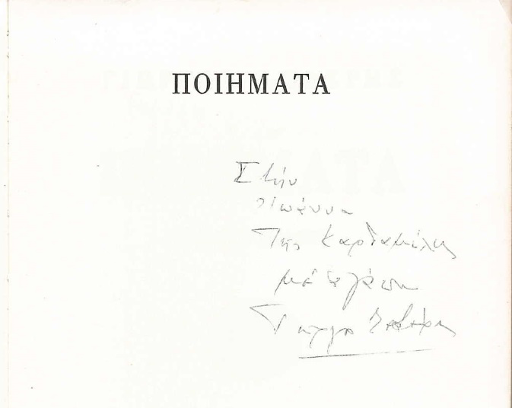

Apart from the many bookcases, books from different periods and places were scattered everywhere in the house30. Among them, the publications dedicated to Paddy and Joan by their author friends hold a special place.